By Mario Telò, President Emeritus of the Institute of European Studies and Member of the Royal Academy of Belgium

By Mario Telò, President Emeritus of the Institute of European Studies and Member of the Royal Academy of Belgium

The greatest democratic exercise in the West, the vote of more than 400 million citizens from 28 countries to elect the only transnational continental parliament, ended with the defeat of the nationalist wave. The risk is, however, that a new majority, composed not only of the EPP-ESP, but also extended to the big winners, the liberals and perhaps even the ecologists, once the worst has been avoided, will abandon themselves to stagnation, to lazy and inertial continuity, without being capable to conduct the profound renewal the EU needs in the next five years.

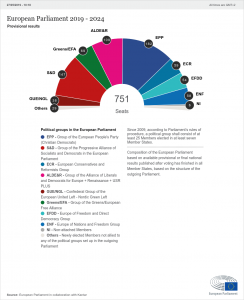

There are many reasons to welcome the results of the European elections on 26 May: not only did Orban, Kaczynski, Salvini and Le Pen’s threat to “conquer Europe” failed, the two European groups together represent only 109 out of 751 EP members, including the British. Their attempt to rebuild alliances and forge an EPP-sovereignist bloc is proving impossible. They will be unable to build a parliamentary majority even in the unlikely event that Merkel’s CDU, the CDH and other Christian groups would accept such a perspective, explicitly desired only by Orban, Kurz, Berlusconi and Tajani. This double failure occurred despite the process of “moderation” of the sovereignists, who, with the sole exception of Farage, abandoned all rhetoric and propaganda for the exit of the EU or the Euro.

The impact of europhobes on the elections

In terms of research, two phenomena are emerging: on the one hand, there is the paradox of British participation in the European elections (3 years after the referendum for Brexit) and, on the other hand, the U-turn of the sovereignists, calling for the transformation of the EU into a Gaullist-type confederation of sovereign countries, rather than for its dismantling. All this seems to confirm the strength and influence of the European institutions’ dynamics, reinforced by 70 years of integration and the existence of a more legitimate European Parliament, thanks to the participation rate, increased by 8 points when compared to 2014.

How can the Europhobes, transformed into Eurosceptic sovereignists, condition the EU, and “change the rules”, as Salvini and Le Pen promised on the evening of the elections they won in their respective countries? Le Pen remains in opposition and, in reality, Salvini is weakened, because his success (from 17% to 34%) is obtained at the expense of his allies: he humiliated his national ally, the “5-star” party (dropped from 32% to 17% in one year), which will probably cause a governmental crisis, as well as his local allies such as Berlusconi’s F.I. who, dropped to 8%, ends his career. What is interesting in both countries is the collapse of what remained of ‘left-wing’ Euroscepticism, and the general hegemony of far-right nationalists in the anti-EU front. This new situation will require the nationalist-Europeanist divide to be articulated with the left and right divide.

How can the Europhobes, transformed into Eurosceptic sovereignists, condition the EU, and “change the rules”, as Salvini and Le Pen promised on the evening of the elections they won in their respective countries? Le Pen remains in opposition and, in reality, Salvini is weakened, because his success (from 17% to 34%) is obtained at the expense of his allies: he humiliated his national ally, the “5-star” party (dropped from 32% to 17% in one year), which will probably cause a governmental crisis, as well as his local allies such as Berlusconi’s F.I. who, dropped to 8%, ends his career. What is interesting in both countries is the collapse of what remained of ‘left-wing’ Euroscepticism, and the general hegemony of far-right nationalists in the anti-EU front. This new situation will require the nationalist-Europeanist divide to be articulated with the left and right divide.

The two Eurosceptic groups in the EP will be isolated, although, through their control of a few national governments, they will be able to appoint Eurosceptic Commissioners and try to block the EU. This may also have an impact on economic and fiscal policy negotiations. In particular, there is a risk of a collision between Italy and the Euro zone on these issues. Italy, in alliance with Poland and Hungary, will also act as’ veto-players’ in the EU Council and the European Council. They will force the Franco-German couple to build a broad alliance for the appointments of the four main EU jobs: President of the European Council, the Commission, the Parliament and the High Representative for Foreign Policy. But, beyond the “veto” card, no common proposal will be possible, because the union between nationalists is an obvious oxymoron: they diverge on the essentials, i. e. foreign policy (pro-Russian and anti-Russian), economic policy (pro and anti-austerity), and migration policy.

Challenges for the future of the EU after the European elections

The real danger would come from an inability of the pro-EU majority to give clear political signs of a major turning point. Both to national public opinions, sometimes confused and dominated by fear, and to the outside, to the members of the ‘iron triangle’ who await the weakening and division of the EU -Trump, Putin and Xi Jinping.

Migration policy, employment policy, especially for young people, and foreign policy will be key issues. It was wrong to say that 2014 was the year of the last chance, as Junker proclaimed, a Juncker whose five-year track record will unfortunately focus more on Hamletian statements of the EU’s “existential crisis” than on his achievements. This time it is even truer than in 2014: if the EU does not have leadership and a shared global vision, if it continues with inertia and muddling through, if it does not give clear signs of initiative for internal cohesion, then common international sovereignty is at great risk of new internal crises, as the global protagonist of multilateralism, in a world that has become more dangerous and competitive.

Photo: European Parliament